Why do we care?

Asthma is a common respiratory condition; attacks are often triggered by environmental conditions such as ozone concentrations, car exhaust, dust mites, roaches, rats and mice, and tobacco smoke. Because exposure to these conditions is a greater problem for poor households than for wealthier ones, asthma is more of a problem in low-income families than in those with the resources to avoid such conditions. It is also a particular problem for children, who are affected both in their every-day activities and in their longer-run ability to develop and thrive, both physically and emotionally. Asthma is an important indicator not only because of the direct problems it causes, but because it is linked to so many other aspects of poverty and environmental health.

How are we doing?

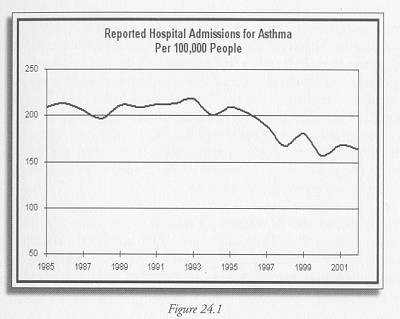

Figure 24.1 shows the number of reported hospitalizations for asthma per 100,000 people, from 1985 through 2002. The state has set a goal of 150 for this indicator, to be reached in 2010. The low for this figure, in 2000, was 157, and it rose to 164 by 2002, so while we are making progress, additional improvement is needed to reach the target. Asthma rates are not evenly distributed among different social groups. In 1998, the most recent year when disaggregated data were available, the rates were 101.3 for whites, 428 for blacks, and 241.6 for Hispanics, and 166 overall.

What is behind these figures?

The decline in hospitalization rates for asthma and the variation across racial and ethnic lines may indicate either a decline in asthma itself and of its triggers, or an improvement in treatment that reduces its severity and thus reduces hospitalizations. The ability to treat asthma has improved greatly, with better inhalers and other medications that actually prevent attacks. The second factor may be more likely to explain the drop in hospitalizations in New Jersey in recent years.

The discrepancies across racial and ethnic lines probably relate both to exposure and to treatment. Blacks and Hispanics are more likely than wealthier whites to be living in unhealthy housing or neighborhoods, where they are disproportionately exposed to the environmental triggers that appear to be associated with asthma. The use of inhalers or other medication to prevent or treat asthma attacks depends on regular access to medical care, however, and an understanding of how to use the medications and the importance of doing so regularly. Again, this may be less readily available to blacks and Hispanics than to whites, so more effective education systems may be needed to reduce the inequity in asthma hospitalization rates.

The state’s strategies to deal with these discrepancies involve a concerted effort to provide information, counseling, and medical care to the most affected populations. These approaches are targeting people in urban areas and children, and are designed in particular to reduce school absenteeism due to asthma attacks and ensure fuller compliance with asthma prevention regimens.

What else would we like to know?

For asthma rates to be a useful indicator, we need to know whether the actual rate of asthma has dropped in recent years. Public responses to the problem will be very different if the trends are due to better access to medication rather than changes in housing or environmental quality.

Figure 24.1 Data provided by Ruth Charbonneau of the Family Health Services Division of the NJ Department of Health & Senior Services. Data on hospital admissions for asthma are based on the New Jersey Uniform Bill-Patient Summary Discharge Files (UB-92), which track causes of hospital admission. Information on obtaining extracts of the UB-92 data may be found at http://www.state.nj.us/health/hcsa/ub92intro.htm.

Indicator Target:

150 hospital admissions for asthma per 100,000 population by 2010

Current (2002) rate:

164

Who set the targets?:

Healthy New Jersey 2010, http://www.state.nj.us/