Why do we care?

Water bird populations are an indicator of the general health of the ecosystems where they live. Water birds are generally at the top of the food chain, so if they are plentiful and healthy, then the marshes and shorelines where they live, as well as the species on which they feed, must also be healthy. They are also good indicators of pollution, because their reproductive systems are sensitive to contamination in their environment. This makes them a “plural indicator species,” meaning that they tell us about their own well-being, that of the other species on which they feed, and the health of the ecosystems on which they depend.

The beaches, bays, and marshes of the Jersey shore are a strong part of our identity. They are an important economic asset, bringing in tourists from across the country. The ecosystems shelter migratory birds that attract birdwatchers from all over the world in spring and fall. The aquatic ecosystems that provide habitat to those birds also filter pollution and sediments from the water. The health of these areas and the species that inhabit them are part of the heritage of New Jersey itself.

How are we doing?

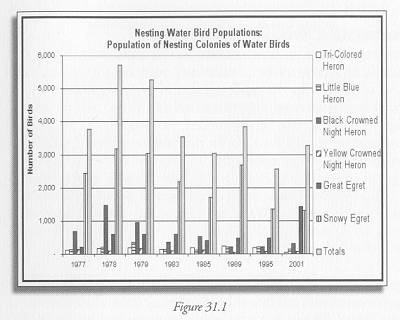

New Jersey’s nesting colonies of water birds have declined over the last twentyfive years. The black bar in Figure 31.1 shows the total population of nesting water birds since the 1970s. While there has been some fluctuation, it has generally declined since its peak in 1978. Some individual species are doing better, particularly great egrets, but most species have declined.

What is behind these figures?

Water birds and humans are in conflict over the same habitat. Human activity diminishes the very features that drew us to the shore in the first place. Human construction of buildings and roads, use of boats that endanger marshes and other vegetation, and pollution of wetlands and bays with chemicals and sediment disturb the birds’ ecosystems. Specific factors contributing to the endangerment of New Jersey birds include loss of nesting habitat to development and erosion, disturbance of nesting activities by beach-goers and their pets, municipal beach maintenance practices that can alter habitat conditions and disturb nesting activities, and excessively high levels of predation exacerbated by human disturbance.

The human threat to water birds is not new. Herons and egrets were once almost wiped out by the millinery trade, when their feathers were prized to decorate hats. They began their comeback when laws were put in place to protect them from hunting and trapping.(1) The National Estuary Program (NEP) was established in 1987 to identify, restore, and protect estuaries and coastal wetlands throughout the United States. NEP targets a broad range of wetland issues, engaging local communities in the protection process.(2) However, the data suggest that these efforts have not been sufficient to protect our water bird populations.

What else would we like to know?

Our data on waterbird populations are updated only erratically, as seen in figure 31.1. Regular updates of these data would give us a better understanding of what is actually happening, and make it easier to know whether trends result from policy reform, land use change, or simply natural variation. A better scientific understanding of the needs of these species would also enable us to identify ways in which human settlements can co-exist with rather than threatening them.

Figure 31.1

Indicator Target:

Targets with which to assess state progress have not yet been established for this indicator.

———-

(1) New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife. Beach Nesting Birds. http://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/ensp/bnb02.htm

(2) EPA. Estuary Programs. http://www.epa.gov/region02/water/nep/